Published: 30 December 2025

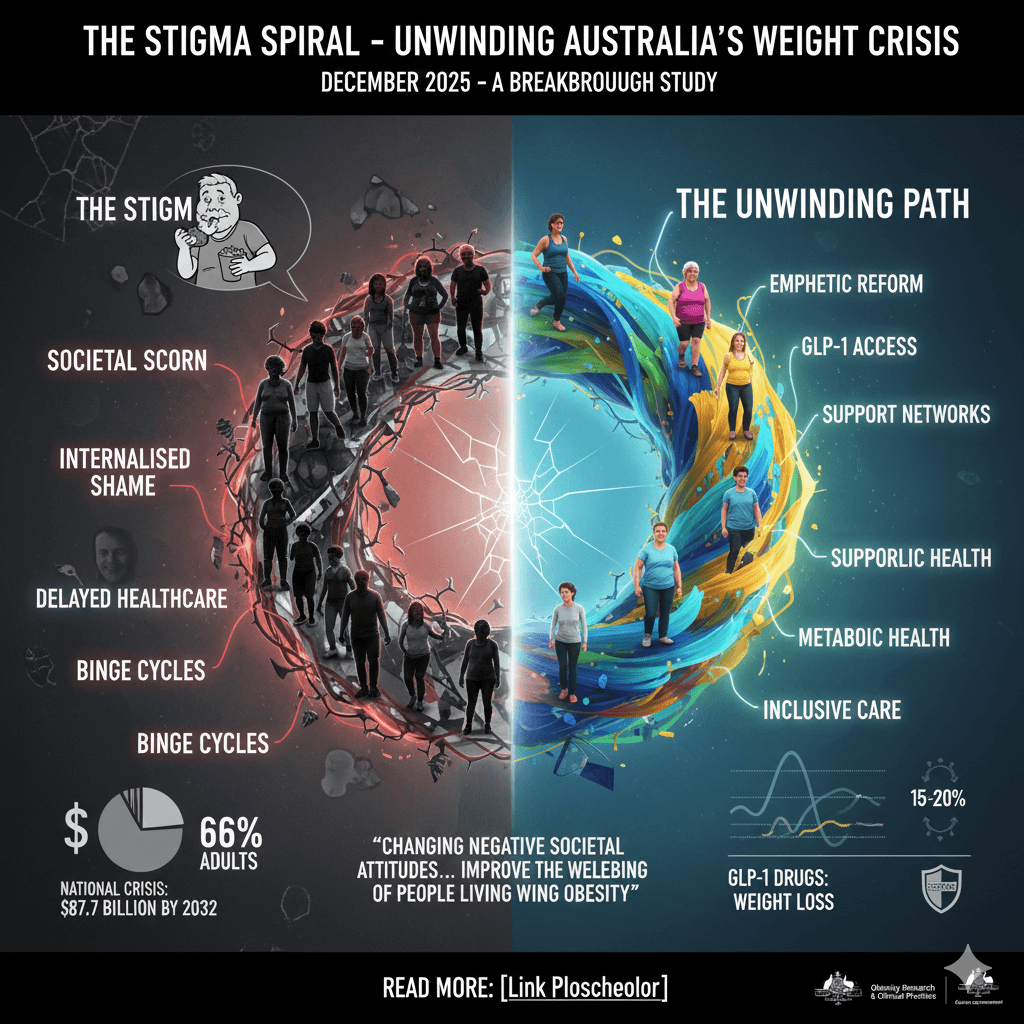

In a nation where two in three adults grapple with excess weight, a hidden epidemic lurks: the shame that silences sufferers and stalls solutions. A groundbreaking December 2025 study reveals that internalised weight stigma affects about two-thirds of overweight Australians, fuelling a cycle of distress and deterred healthcare. As the government mulls subsidising revolutionary GLP-1 drugs amid soaring obesity costs, it’s time to unravel this spiral – from societal scorn to personal pain, and towards empathetic reform.

Outer Coil: The Societal Snapshot

Two in three Australians carry extra weight – and an invisible burden of shame. The latest research from Obesity Research & Clinical Practice, published mid-December 2025, spotlights internalised weight stigma as a pervasive barrier, where individuals absorb negative stereotypes, leading to poorer mental health and avoided medical care

This isn’t just a personal plight; it’s a national crisis. Obesity drains the economy, with direct and indirect costs hitting $11.8 billion in 2018 and projected to balloon to $87.7 billion by 2032 if unchecked. Recent figures peg overweight and obesity as contributing $7 billion to health spending in 2023–24 alone.

Nationally, around one-third of adults are obese, with another third overweight – a prevalence of 66% that demands action. Yet public discourse often veers into blame. As one X user quipped, echoing persistent stereotypes:”The proposal here is that stigma and shame prevent people from taking steps to look after a problem many created and continue to feed and are too lazy to do anything about.” Such views, rooted in outdated notions debunked by Curtin University research in 2023, paint those with obesity as “lazy” or “gluttonous,” ignoring complex factors like genetics, environment, and socioeconomics.

To contextualise, here’s a comparison of obesity rates:

| Country | Adult Obesity Rate (2025 Estimates) | Source |

| Australia | ~31% | World Population Review, Global Obesity Observatory |

| United States | ~42% | World Population Review |

| United Kingdom | ~28% | ZAVA UK, Global Obesity Observatory |

These figures underscore Australia’s mid-tier ranking globally, yet highlight the urgency amid rising trends.

Descending Twist: Internalised Impacts

Delving deeper, personal stories illuminate the toll. On X, users share raw anecdotes: one recounts gaining weight from internalised trauma, trapped in binge cycles without a formal eating disorder diagnosis, yet blaming societal pressures and self-deception. Another fears reverting to a “normal” BMI, haunted by past stigma: “I spent my youth desperate to lose weight… ironically it wasn’t until I stopped dieting that I stopped gaining.”

The study’s core findings are stark: internalised stigma mediates the effects of experienced bias on psychosocial health, affecting two-thirds of overweight adults and linking to heightened distress, body dissatisfaction, depression, and anxiety. This echoes the economic reprise: avoided healthcare exacerbates costs, with obesity-linked mental health issues amplifying the $11.8 billion burden.

Health ripple effects include:

- Higher psychological distress and depressive symptoms.

- Increased risk of eating disorders, like binge eating.

- Reduced treatment adherence and social isolation.

- Lower self-esteem and body image concerns.

Core Knot: The Stigma Mechanisms

At the spiral’s heart lies how stigma operates: experienced bias (from media, family, or healthcare) morphs into internalised shame, where individuals self-blame as “lazy” or lacking willpower. The study notes misconceptions, like supernatural beliefs as predictors of stigma, compounding the issue.

Balancing views, academics advocate inclusive care: “Weight stigma negatively affects mental health while it seems to be a more significant contributor to psychosocial distress compared to obesity per se.” Yet public scepticism persists, debunking myths like “fat shaming works” – research shows it heightens stress, not solutions. On X, counterpoints emerge: “The more people talked about my weight, the more I gained because I was depressed The change came from internal motivation.”

A comparison table of predictors:

| Stigma Predictors | Protective Factors |

| Poor social support | Strong relationships (“longevity drug”) |

| Side effects from meds | Psycho-educational programs |

| Supernatural aetiological beliefs | Weight-inclusive healthcare |

| Experienced discrimination | Emotional support networks |

Unwinding Path: Policy and Solutions

Momentum builds for change. The government debates subsidising GLP-1 drugs like semaglutide (Ozempic, Wegovy) and tirzepatide (Mounjaro), which deliver 15-20% weight loss in trials. Pros include easing obesity’s strain; cons flag side effects, mental health risks (affecting up to 2% of users), and telehealth overprescription. The PBAC recommends phased PBS inclusion for high-risk cases.

Innovative ideas: Psycho-education to dispel myths, second-generation antipsychotics for co-morbid conditions, and community programs like virtual body image exercises. Reimagining an X story: One user’s binge cycle, tied to trauma, could break with support – “Accepting my state and focusing on altering the internalised mindset is actually the only time I’ve ever made massive external change.”

Steps for readers:

- Build support networks to combat isolation.

- Challenge biases through education.

- Seek weight-inclusive care.

- Prioritise metabolic health over shame.

Ascending Release: Future Horizons

Envision a stigma-free Australia: Reduced costs, bolstered mental health, and inclusive policies slashing the $87.7 billion projection. Reflect on biases – as one expert notes, “Changing negative societal attitudes… would improve the wellbeing of people living with obesity.”

Pull-Quote Gallery:

- “Weight stigma is associated with a range of poor psychological outcomes…” – Frontiers in Psychiatry.

- “It’s about gaining health, not just losing weight.” – RACGP.

- X user: “If you throw enough responsibility onto yourself you can transmute the subconscious fear…”

- Policymaker: “The inclusion of GLP-1 medications on the PBS should be done at a controlled pace.” – PBAC.